History Of The Arctic Refuge Struggle

Drawn largely from the narrative of Defending the Arctic Refuge, this page offers an overview of key events in the history of the Arctic Refuge struggle. You can find links to speeches, publications, documentary films, government reports, websites, and other sources at the bottom of many of the entries.

Since Time Immemorial: The Long History Of The Gwich’in Homeland

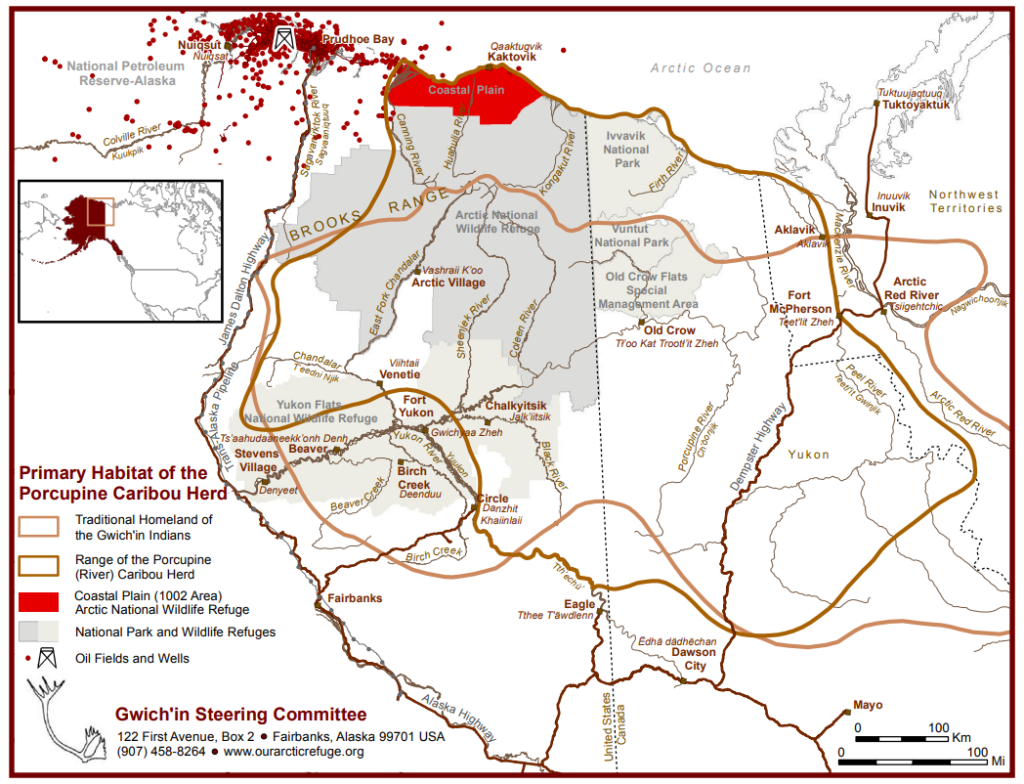

The Gwich’in creation story tells of a time when only animals roamed the earth. Eventually, people arose out of animals, and the Gwich’in came from the caribou. When that happened, Gwich’in and caribou made a promise to protect and sustain one another. In recent decades, though, this relationship has been threatened by ongoing efforts to drill in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge—the calving grounds of the Porcupine caribou herd. For Gwich’in in Alaska and Canada, the fight to protect the Arctic Refuge from oil drilling is also a struggle for their food security and cultural survival.

Photo Credit: Lenny Kohm, 1988

Early Years Of Alaska And The Refuge

Compared to the long history of Gwich’in life in the region, Alaska as we know it came to be only a short time ago. Resource extraction quickly became the state’s dominant economic model, but several groups sought to protect the region from intensive development and oil interests. While the mainstream conservation movement tried to preserve these lands as America’s last frontier—often disregarding the concerns of Alaska Natives along the way—the Gwich’in and other Indigenous nations began a tradition of political resistance to protect their ways of life.

1867

Alaska Purchased From Russia By the United States

After being stolen by Russia in the eighteenth century, Alaska was then sold to the United States in 1867. This purchase was part of a broader push for American colonial expansion during the nineteenth century. US leaders were motivated by economic opportunity in the region, seeking access to the lucrative seal trade and the potential for a convenient trade route to Asia. The Gwich’in and other Indigenous nations who had long stewarded these lands had no say in the acquisition or transfer of this vast territory. The US government’s indifference to Indigenous sovereignty in the face of economic interests would continue as demand for fossil fuels grew in the twentieth century.

1911

Boundary Between Alaska And Yukon (US And Canada) Is Solidified

The settler nations of Canada and the United States sent a joint survey party through Gwich’in territory to extend the boundary line along the 141st meridian. The hardening of boundaries, together with new regulations and duties, bisected the Gwich’in Nation, making travel across the international border to visit family members and share country foods increasingly difficult. The extension of the boundary coincided with other forms of colonial violence, including residential schools that sought to suppress Gwich’in language and culture as well as attempts by the state to turn their homelands into sites of resource extraction.

Map Credit: Gwich’in Steering Committee

1950s

Porcupine Caribou Herd Is Named By Biologists

Using bush planes to study the distribution of caribou in the Arctic, US and Canadian biologists divided the caribou population into herds based on their calving grounds and migration routes. The Porcupine herd was named after the river that this group of caribou cross on their annual journey to calving grounds on the Arctic coastal plain. Scientific studies of caribou and other wildlife would later become embroiled in the political battle over the Arctic Refuge.

Photo Credit: Fran Mauer, 1986

1953

“Northeast Arctic: The Last Great Wilderness” Published In The Sierra Club Bulletin

In the piece, George L. Collins and Lowell Sumner advocated for protecting the northeast corner of Alaska, along with adjacent land in the Yukon, from development. They hit upon an evocative phrase to describe the area: “the last great wilderness.” The article played a crucial role in inspiring wilderness advocates and conservation groups to campaign for the protection of what later became the Arctic Refuge. But the piece also relied on frontier mythology to frame perceptions of Alaska, erasing the presence and culture of the Gwich’in and other Indigenous communities.

1956-1960

First Efforts By American Conservationists To Protect The Northeastern Corner Of Alaska

Inspired by Collins and Sumner’s 1953 article, the Wilderness Society, Sierra Club, and other conservation groups campaigned for the establishment of an Arctic wildlife reserve. Like Lenny Kohm did later, these conservation activists used images to build grassroots support. Following their 1956 expedition to the Sheenjek River Valley, Olaus Murie and other advocates presented slide shows and documentary films to grassroots audiences. While Kohm and Gwich’in leaders later emphasized the human rights issues at stake in the Arctic, 1950s advocates instead hewed to traditional colonial ideas of wilderness as pristine, untouched nature.

Watch a 1959 Arctic campaign video >

1959

Alaska Becomes A State

President Dwight D. Eisenhower established the 49th state with the Alaska Statehood Act. Although this legislation was soon followed by the creation of an Arctic wildlife area, the act also further incentivized efforts to drill oil on federal lands by requiring 90% of resulting revenue to be returned to the state.

1960

The Arctic National Wildlife Range Is Created

The newly elected, pro-development Alaska delegation blocked Congressional legislation for protecting northeastern Alaska. The Eisenhower administration responded by issuing an executive order to create the 8.9 million acre Arctic National Wildlife Range. Public Land Order 2214 called for the protection of this area to preserve its “unique wildlife, wilderness and recreation values.” The order said nothing of the Indigenous peoples who had long stewarded these lands.

Photo Credit: Subhankar Banerjee, 2002

1964

Congress Passes The Wilderness Act Of 1964

A milestone in federal environmental law, this act created a national wilderness system. Fusing conventional ideas of untouched nature with a more ecological perspective on the interdependence of living things, the act defines wilderness as areas “where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” Like other colonial framings of nature, though, this definiton ignores the long history of Indigenous occupancy and stewardship of the continent.

Read the Wilderness Act >

1964-1967

Gwich’in Communities And Conservation Allies Defeat The Rampart Dam Proposal

In 1964, Gwich’in leaders formed Gwitchya Gwitchin Ginkhye (Yukon Flats People Speak) in a campaign against this proposed US Army Corps of Engineers dam project. The dam would have flooded seven Indigenous villages along with vast stretches of unique habitat in the Yukon Flats. In their opposition, Gwich’in leaders—along with their conservation allies—emphasized the ecological and human significance of the area. Eventually, they defeated the proposal, establishing an important precedent for Gwich’in environmental organizing in the future.

The Threat Of Oil Extraction Grows

Though activists had made strides towards protecting lands in northeastern Alaska during the fifties and sixties, the coming decades would intensify efforts to extract fossil fuel resources in the region. In response to these pressures, the Alaska Coalition and other groups would organize one of the most significant public lands campaigns in US history.

1968

Atlantic Richfield Company Discovers Oil At Prudhoe Bay

The discovery of the largest oil field in North America would spark an oil boom in the state and spark interest in constructing a massive pipeline. It would also intensify speculation as to whether even more fossil fuels could be extracted from the North Slope of Alaska—including the Arctic National Wildlife Range.

Photo Credit: Pamela A. Miller, 1988

1969

Wilbur Mills Travels To The Arctic National Wildlife Range To Photograph The Land And Wildlife

Seattle-based photographer Wilbur Mills was invited by Averill Thayer, the first manager of the Arctic Range, to document the breathtaking scenery and wildlife of the area. These photos—along with images from subsequent visits—celebrate the unique qualities of the Arctic Range and would circulate in conservation magazines throughout the 70s and 80s. Several of Mills’s photos would also be selected by Lenny Kohm to appear in The Last Great Wilderness slide show.

Photo Credit: Wilbur Mills, 1969

1971

Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) Signed Into Law

ANCSA was passed in the midst of efforts to expand fossil fuel extraction and build a pipeline through Indigenous lands. The legislation established Native-owned corporations in the state. As the largest land claims settlement in US history, the law transferred 10% of Alaska’s acreage to the corporations, at the cost of extinguishing Native title to land. Many Alaska Natives saw the law as part of an assimilationist push to erode the sovereignty of their tribes. Others viewed it as an important source of economic prosperity, with an initial payout of $962 million and 44 million acres of land to the corporations. In the decades ahead, Native corporations created by ANCSA would contribute in important—and controversial—ways to the fight over the Arctic Refuge.

1970s

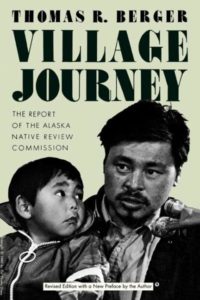

Thomas Berger Conducts The Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry

The Mackenzie Valley Pipeline would have transported natural gas from Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, to southern markets, cutting through northeastern Alaska, Yukon, and the Northwest Territories along the way. In 1974, the Canadian government appointed jurist Thomas Berger to investigate the potential impacts of the project. Berger did something unexpected: he prioritized the concerns and voices of Indigenous peoples. Berger held hearings in 35 Indigenous villages in the Yukon and Northwest Territories, collecting testimony in seven different languages. Gwich’in and other Indigenous communities in the affected area used the opportunity to oppose the extractive practices of settler colonialism. Their testimony was quoted directly in Berger’s Northern Frontier, Northern Homeland report, which emphasized the importance of heeding Indigenous voices and called for a ten-year moratorium on the pipeline to protect caribou and the ways of life they support. As with their opposition to the Rampart Dam in Alaska, the Gwich’in again became involved in a crucial struggle to sustain their culture, identity, and food security.

1971

Fairbanks Environmental Center Is Formed

The Fairbanks Environmental Center was formed in Fairbanks, Alaska, as the first Alaska-based environmental organization working on Arctic issues. The group later changed its name to the Northern Alaska Environmental Center and continues to play a vital role in the Arctic Refuge struggle.

Learn more about the Northern Alaska Environmental Center >

1975-1977

Building Of The Trans-Alaska Pipeline

Following the OPEC oil embargo of 1973-74, the plan to build a pipeline to transport oil from Prudhoe Bay quickly gained federal approval. Completed in 1977, the Trans-Alaska Pipeline carries oil from the North Slope to the port city of Valdez, Alaska, 800 miles to the south. Since its construction, the effort to keep oil flowing through the massive pipeline has motivated pushes to drill the Arctic Refuge and other sites in northern Alaska.

Photo Credit: Philip Wight, 2017

Learn how the Trans-Alaska Pipeline has fueled interest in drilling the Refuge >

1970s

Wilbur Mills Calls For Expansion And Permanent Protection Of The Arctic National Wildlife Range

Mills was inspired by his 1969 trip to become an Arctic activist, especially as the drilling threat increased during the 1970s. Throughout the decade, he wrote a series of reports calling for the expansion of the Range to 19 million acres—twice its original size—and for the full area to be granted permanent wilderness status. Like his photos, these reports circulated among mainstream conservation groups and contributed to the campaign for protection of Alaska’s public lands.

Late 1970s

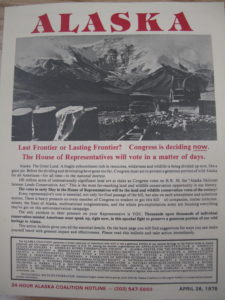

The Alaska Coalition Campaigns In Support Of H.R. 39

With the election of pro-conservation Democrat Jimmy Carter in 1976, the Alaska Coalition ramped up its public lands campaign and called for the Arctic coastal plain to be granted wilderness status. Wilderness advocates hitched the measure to H.R. 39, an omnibus bill that included other provisions to expand national parks, forests, and wildlife refuges in Alaska. Knowing that grassroots support was essential to ensuring the bill’s success, the Sierra Club, the Wilderness Society, Friends of the Earth, and other groups produced slide shows and accompanying scripts for grassroots organizers to present around the nation. The bill passed the House twice with huge margins, demonstrating the effectiveness of grassroots visual culture.

December 1980

Passage Of Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA), Including Controversial Section 1002

Though it passed in the House, H.R. 39 stalled in the Senate because of opposition from Ted Stevens, one of Alaska’s senators, and other proponents of Arctic drilling. Anticipating a shift toward environmental deregulation with the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980, the Alaska Coalition was forced to compromise on a new bill. ANILCA expanded the renamed Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to 19 million acres and created millions more acres of national parks, forests, and wildlife refuges. However, Section 1002 of the bill designated a 1.5-million-acre area of the coastal plain as a special study area and left its fate in legislative limbo, authorizing a future Congress to determine whether it should be protected as permanent wilderness or turned into an industrialized oil field. This land, which included the calving grounds of the Porcupine caribou herd, would soon become one of the most contested places in all of North America.

Read the Act >

A Grassroots Movement To Protect The Arctic Refuge Is Born

The election of Ronald Reagan brought with it renewed interest in drilling the Arctic Refuge coastal plain. But as threats to the Refuge grew, so did efforts to protect it. The Gwich’in scaled up their organizing efforts, Lenny Kohm and friends founded the Sonoma Coalition, and scientists in federal agencies became whistleblowers when their findings were distorted to justify drilling. Eventually, an unlikely coalition of Refuge defenders came together to create The Last Great Wilderness slide show, and with it, helped build the grassroots movement that would define the fight for the Refuge.

1980s

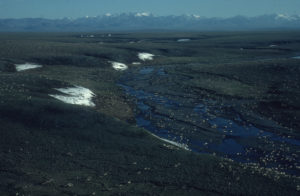

Fran Mauer And Other US Biologists Conduct Studies On Caribou Calf Mortality

As stipulated by ANILCA, scientists with the US Fish and Wildlife Service research the potential impact of development on the 1002 area. Mauer and other researchers would conduct more than fifty studies by 1987. Taken together, the research left little doubt that oil development on the coastal plain would seriously disrupt the annual calving of the Porcupine caribou herd.

Photo Credit: Wilbur Mills, 1969

1983-1985

Thomas Berger Visits Alaskan Native Communities To Study Effects Of ANCSA

Thomas Berger, who conducted the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry in Canada in the 1970s, was invited by the Inuit Circumpolar Council and the World Council of Indigenous Peoples to help conduct the Alaska Native Review Commission in the 1980s. He visited Indigenous communities across the state and listened to Native opinions on ANCSA in a way that the US government never did before enacting the policy. Many expressed to Berger that they felt the law was illegitimate, and that it disregarded Indigenous cultural values and undermined the sovereignty of tribal governments.

1984

Creation Of Northern Yukon National Park (Later Ivvavik National Park)

The Inuvialuit Final Agreement with the Canadian government was the first land claims agreement to create a national park. The park protected caribou calving grounds on the Canadian coastal plain, and unlike most North American parks, it ensured Indigenous rights to hunt and fish within its boundaries, allowing the Inuvialuit to sustain their customs and subsistence practices. The park was later renamed Ivvavik, an Inuvialuktun word meaning “a place for giving birth, a nursery,” to honor its role in protecting caribou calving grounds.

1985

Founding Of The Porcupine Caribou Management Board

Composed of representatives from First Nations, the Canadian government, and the governments of the Yukon and Northwest Territories, the PCMB protects and cares for the Porcupine caribou herd and its habitat, a mission essential to sustaining Indigenous ways of life in the region. Responding to efforts to drill the Arctic Refuge, the PCMB would later help select and fund Gwich’in representatives who toured with Lenny Kohm and the Last Great Wilderness show.

Learn more about the PCMB’s work >

August 1986-April 1987

Science On The Potential Harms Of Drilling The Refuge Distorted In Federal ‘1002 Report’

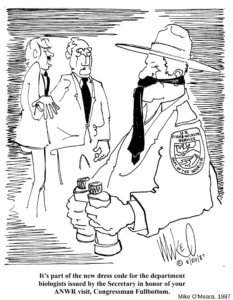

Stipulated by the 1980 ANILCA policy, the report was supposed to be the culmination of the studies conducted by Fran Mauer and other USFWS biologists on the potential impacts of development on the caribou and other wildlife that depend upon the Arctic coastal plain. But Don Hodel, Reagan’s Secretary of the Interior, had other plans. His section, titled “Secretary’s Recommendations,” blatantly contradicted the scientific evidence that drilling would severely impact caribou populations. The final report, released by the Interior Department in 1987, ignored data and tampered with the findings of the department’s own biologists to conclude that “caribou [could] coexist successfully with oil development.”

Read the report >

July 1987

The US And Canada Sign A Bilateral Agreement On The Porcupine Caribou Herd

The result of transnational Indigenous advocacy, this bilateral agreement between the United States and Canada recognized the significance of the Porcupine caribou herd to Indigenous communities on both sides of the border. The two nations also pledged to cooperate on conserving the transboundary habitat of the herd.

See the agreement >

Summer and Fall 1987

Lenny Kohm And Glendon Brunk Join The Refuge Struggle

As the Reagan administration pushed its proposal to develop the coastal plain, Lenny Kohm journeyed from his home in Sonoma, California, to Alaska to take photos for an Audubon magazine piece about the Arctic Refuge. After spending time in Gwich’in communities, Kohm had an epiphany that would inspire him to become an Arctic activist. Around the same time, Glendon Brunk had his own epiphany in the North Slope of Alaska, hoping to make a documentary film on the issue. By the fall of 1987, Brunk was also living in the Sonoma area, where he joined Kohm’s newly formed Sonoma Coalition for the Arctic Refuge. Kohm also traveled to Washington, DC, that fall to testify about the Arctic Refuge before the US Senate. He emphasized the human rights issues at stake and the importance of listening to Gwich’in voices.

Read Kohm’s Senate testimony >

December 1987-May 1988

Pamela A. Miller Becomes A Whistleblower

Following the controversy over the “1002 report,” congressional Democrats requested an additional report comparing the actual and predicted environmental impacts of oil development on Prudhoe Bay. Rather than release the full report, Reagan’s Interior department instead sent Congress a heavily distorted 4-page summary that contradicted the actual findings. Dismayed at the suppression of her work, USFWS biologist Pamela A. Miller leaked the full report to the New York Times, resulting in accusations of corruption aimed at the Reagan administration.

Image Credit: Mike O’Meara, 1987

February-August 1988

Relationship Develops Between Gwich’in And Sonoma Activists

Following Kohm’s epiphany in 1987, Norma Kassi, a leader of the Vuntut Gwitchin community in Old Crow, invited him to her village to learn more about their ways of life and connection to the Arctic Refuge. Kohm reciprocated in early 1988 by inviting Kassi to Sonoma. Her time with the Coalition helped its other members better appreciate the relationship between the Gwich’in and the Arctic Refuge. That May, Kohm journeyed to Kassi’s family hunting camp at Crow Flats, north of Old Crow. On this trip, he would take many photos for the Last Great Wilderness slide show and would continue to build trust with and learn from the Gwich’in. In August, nine other members of the Sonoma Coalition would join him to continue developing this bond.

Photo Credit: Finis Dunaway, 2017

May 1988

Audubon Magazine’s Special Issue On The Arctic Refuge Features Kohm’s Photographs

Though Kohm took many photos that featured Gwich’in communities and their ways of life, only one of these photos appeared in the special issue. Like most of the mainstream Refuge advocacy up to that point, Audubon barely acknowledged Gwich’in connections to caribou and the Refuge and instead framed this place as an enchanted wilderness enclave.

Photo Credit: Lenny Kohm, 1987

June 1988

The Gwich’in Gather In Arctic Village, Alaska

In response to the Reagan administration’s drilling plans, Gwich’in leaders convene a gathering of their communities in Arctic Village, Alaska. Though non-Indigenous activists (including Kohm) attended, Gwich’in Niintsyaa, “a gathering of the people,” was planned and led by Gwich’in leaders, featured only Gwich’in speakers, and was conducted in the Gwich’in language. Many regard the gathering as a moment of rebirth for the Gwich’in nation.

Photo Credit: Lenny Kohm, 1988

June 1988

The Gwich’in Steering Committee Is Founded

At the end of the Gwich’in Niintsyaa, leaders from each of the communities came together to pass two resolutions: the first called upon Congress to grant wilderness status to the Arctic coastal plain, and the second created the Gwich’in Steering Committee to serve as a transnational political advocacy group. To this day, the committee continues to lead Gwich’in advocacy efforts to protect the Arctic Refuge.

Photo Credit: Keri Oberly, 2018

Read the Gwich’in Resolution about the Arctic Refuge >

Learn more about the Gwich’in Steering Committee >

June 1988

Jonathon Solomon Testifies Before Congress About Gwich’in Support For Wilderness Designation Of The Coastal Plain

Following the Gwich’in Gathering, Jonathon Solomon traveled to Washington, DC, to testify before a House committee. He emphasized many of the key messages of the Gathering, including the call for the Arctic Refuge to be designated as wilderness. But he stressed that the Gwich’in did not see wilderness as a place where people were only visitors. He explained that the cultural customs of the Gwich’in had long been part of that land and its ecology, and that they must be permitted to continue to hunt, fish, and trap in the Refuge regardless of its legal status.

Read Solomon’s House testimony >

Fall 1988

The Last Great Wilderness Slide Show Is Assembled At Kohm’s Art Farm Studio In Sonoma

On their return from Old Crow, the Sonoma Coalition began to develop a new tool for grassroots advocacy, drawing on Kohm’s photos and their recent experiences in the Arctic. The show used a fade-dissolve unit, allowing slides to gradually fade in and out, and synchronizing with a score created by Richard Dale, along with a script written by Brunk and narrated by Jane Zimmerman. The slide show would form the basis of Kohm’s advocacy efforts over the next two decades, introducing grassroots audiences to the Arctic Refuge and its importance to the Gwich’in way of life. Kohm and Brunk toured together into early 1989, until a grant from Patagonia allowed the Coalition to duplicate the slide show and divide their efforts.

Watch the slide show >

Late 1988

Lenny Kohm Meets Harvard Ayers And Receives Support From Sierra Club

Kohm met Ayers at one of the first Last Great Wilderness presentations in San Francisco. Founder of the Sierra Club’s Native American Sites Committee and a leader of its Blue Ridge group, Ayers immediately took an interest in Kohm and his activism. With Ayers’s support, Kohm began to receive funding from the Sierra Club.

1989

Glendon Brunk Receives Support From Northern Alaska Environmental Center

Brunk struggled to find a sponsor for his own slide show tour. He eventually approached the Northern Alaska Environmental Center in Fairbanks, and gained the enthusiastic support of this small grassroots group. With Brunk and Fairbanks-based activists giving presentations across the country, the Last Great Wilderness slide show became the primary outreach tool for the Northern Center’s Arctic Refuge campaign.

March 24, 1989

The Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Devastates The Southern Coast Of Alaska

As the Reagan years came to an end without a successful drilling bill, Arctic drilling proponents prepared to redouble their efforts with the support of incoming president and oilman George H. W. Bush. But just as Bush took office and a drilling measure moved through committee, the Exxon Valdez oil carrier slammed into a reef off the southern coast of Alaska. With oil that had flowed through the Trans-Alaska pipeline now spread across the Alaskan coast, this enormous spill devastated ecosystems and wildlife. The fallout from the disaster also killed, for a short time, efforts to open the 1002 area to drilling.

The Fight For The Refuge In The 1990s

Though the Exxon Valdez spill stymied drilling interests for a time, the beginning of the Persian Gulf War in 1991 would quickly rekindle efforts to open the Arctic Refuge. Moreover, the Republican Revolution of 1994 transformed the political landscape and led, for the first time, to the passage of a drilling measure by the full Congress. At the same time, the Gwich’in Steering Committee, environmental activists, and others continued to build a diverse, grassroots movement to defend the Refuge.

1990

Gwich’in Steering Committee Gains Support Of Episcopal Church And Other Religious Organizations

With drilling interests riding out the fallout of the Exxon Valdez spill, the newly formed Gwich’in Steering Committee wasted no time in publicizing their cause. One of their most successful efforts was a piece published in People magazine six months after the spill. The piece resonated with Alaskan Episcopal minister Scott Fisher, who devoted himself to the cause and helped Trimble Gilbert and other Gwich’in push the Alaskan diocese to adopt a resolution against Arctic drilling. After that, religious support snowballed as more and more churches and faith groups came to understand how the refuge debate was also a question of human rights and Indigenous cultural survival.

Read about the Diocese of Alaska’s resolution against Arctic drilling >

January 1991

Persian Gulf War Begins

After Saddam Hussein’s Iraq invaded Kuwait in August 1990, Bush retaliated by launching the Persian Gulf War in January 1991. The fossil fuel lobby and pro-drilling politicians quickly began to frame the war as a justification for opening the Arctic Refuge to drilling.

Spring 1991

Johnston-Wallop Bill Proposed In The Senate

Increased pro-drilling sentiment culminated in a provision for Arctic Refuge drilling attached to the 1991 Johnston-Wallop bill in the Senate. In May, the bill sailed through the Energy and Natural Resources committee with a 17-3 vote. With a full vote looming in November, Arctic Refuge defenders kicked their advocacy efforts into high gear to block it.

Watch the Senate committee hearing on the bill >

Summer and Fall 1991

Kohm And Gwich’in Representatives Tour With The LGW Slideshow

Photo Credit: Pamela A. Miller, 1995

Fall 1991

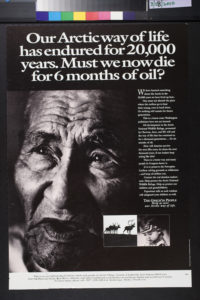

Our Arctic Way Of Life Poster Highlights Gwich’in Voices In The Fight Against The Johnston-Wallop Bill

In the lead-up to the vote on the Johnston-Wallop bill, the Gwich’in Steering Committee continued to form new partnerships and reach new audiences. Working with the Public Media Center, the committee produced a full-page newspaper ad and large-format posters to display at bus stations in DC. The ad features the face of Gwich’in Elder Isaac Tritt, seemingly in mid-speech, along with text that contrasts the long history of Gwich’in culture and knowledge in the region to the mere 6-month supply of oil that would come from drilling the Refuge.

November 1, 1991

Johnston-Wallop Bill Fails In The Senate

As the November vote approached, Minnesota’s Paul Wellstone and other anti-drilling Senators filibustered the Johnston-Wallop bill, which meant that it would require a 60-vote majority to pass. In the last days of October, refuge defenders mobilized their grassroots network, encouraging concerned citizens to contact their Senators and express their opposition to the bill. The November 1st vote fell ten votes short—a resounding victory for Arctic Refuge defenders and a testament to the power of grassroots organizing.

Read the transcript of Senator Wellstone’s speech >

1993

Alaska Wilderness League Formed

As the only DC-based conservation organization that focuses solely on Alaskan issues, the Alaska Wilderness League would be central to pro-Refuge advocacy when the threat of Arctic drilling resurged in the mid-1990s and beyond.

Learn more about the Alaska Wilderness League >

1993

Vuntut National Park Is Created By The Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation Final Agreement

Mirroring the Inuvialuit Final Agreement of 1984, this agreement between the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation and the Canadian government created a national park just south of Ivvavik. By including harvesting rights and comanagement provisions, the agreement embedded Indigenous values and voices into the park. With both parks bordering the Arctic Refuge, the result was a “vast transnational nursery” for caribou and other wildlife species.

Learn more about Vuntut National Park >

Fall 1994

The Republican Revolution Creates A Pro-Drilling Congress

The Republican takeover of Congress in the 1994 midterms caught many in the conservation community off guard. GOP candidates had promised to “restore fiscal responsibility” as part of their ten-point “Contract with America” plan. Under new Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich, Republicans in both chambers prepared the way for new drilling provisions. This process included the appointment of pro-development members of the Alaska delegation to chairs of natural resources committees in both the Senate and the House.

Early 1995

Republican Majority Proposes Budget Bill With Arctic Refuge Drilling Provision

Despite their newfound power in Congress, drilling proponents thought they would be unable to pass a bill with the sole purpose of opening the 1002 area. Instead, they included it as a provision in the 1995 budget bill. This would prevent the measure from being filibustered, requiring only a 50-vote majority to pass the Senate. Though proponents framed the provision as a way to balance the budget by leasing the land to oil companies, their own, likely inflated estimate suggested that it would have brought in only $1.3 billion—scarcely offsetting the GOP’s plan to lower taxes by $245 billion and slash federal spending by $894 billion.

June 1995

Youth Environmental Summit In Loveland, Colorado

As a vote over the Arctic drilling provision loomed, Kohm brought The Last Great Wilderness slide show to new audiences. His presentation to more than 300 teenagers at the Youth Environmental Summit in Colorado would be particularly significant. The involvement of Gwich’in speakers made the issue come alive for a younger generation. Following the event, Colorado Senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell, a need-to-switch target for the refuge campaign, lashed out at Kohm for critical comments he had made about the Senator’s recent support of drilling.

Watch Kassi’s speech and Kohm’s comments before and after presenting the slideshow >

November 1995

Clinton Vetoes Budget Bill And Allows Two Government Shutdowns In Opposition To Drilling Provision

The Alaska Coalition, now led by former USFWS whistleblower Pamela A. Miller, coordinated a fierce campaign against the Arctic drilling provision in the 1995 budget bill. Earlier in the year, a vote to remove the provision had failed by a margin of 44 to 56. But by October, after months of intense advocacy and campaigning, a second vote came much closer with a 48-51 tally. Given the immense odds, refuge defenders hailed the progress as a victory. They hoped that the shift in momentum would convince President Bill Clinton to veto the budget to protect the Arctic Refuge. Though Clinton’s support remained in doubt, the president did eventually veto the bill.

2000

Attendees Of The 1995 Youth Environmental Summit Are Featured In Arctic Quest: Our Search For Truth

Directed by summit attendee Jeffrey Barrie, the film features several other participants on a trip to Alaska and Old Crow, Yukon, the year after the summit. Later, Barrie and fellow summit attendee Alex Tapia followed Kohm’s model in touring with slides and videos from their trip. They toured again with the completed film in 2000, and Barrie would continue advocating for the Arctic Refuge as a field organizer for the Alaska Wilderness League in the 2000s.

Defending The Arctic Refuge In Post-9/11 America

The election of George W. Bush, along with the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, led to renewed efforts to drill the Arctic Refuge. In response, a new generation of unlikely activists joined the refuge struggle. This included Indian-born photographer Subhankar Banerjee and many Indigenous leaders, who continued to build and expand alliances with grassroots activists and environmental groups.

Winter 2001

Subhankar Banerjee Takes His First Trip To The Arctic Refuge

Banerjee’s visit started as a documentary photography project intended to emphasize the ecological life of the Arctic Refuge by capturing it in each season. But with Iñupiat Robert Thompson as his guide, he quickly saw that the area was more than a scenic, biodiverse wilderness. He began to understand it—and portray it through photographs—as the homeland of Iñupiat and Gwich’in communities, and as an ecological space connected to places far beyond the northeastern corner of Alaska. Following that trip, Banerjee would become a key advocate for protecting the Arctic Refuge.

Photo Credit: Subhankar Banerjee, 2001

September 11, 2001

9/11 Upends The American Political Landscape

The 9/11 terrorist acts shook Americans and others across the world. This was certainly true for several Gwich’in representatives who were advocating in defense of the Arctic Refuge at the US Capitol that morning. The aftermath of the attacks would intensify threats to the Arctic Refuge.

October 2001

Fran Mauer Exposes Secretary Of The Interior Gale Norton’s Manipulation Of Caribou Calving Report

After drafting a report on the calving range of the Porcupine herd for the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, Mauer was dismayed to find that George W. Bush’s Secretary of the Interior Gale Norton had changed the report to downplay the potential impacts of drilling on the herd. Having endured the suppression of his work as a Fish and Wildlife biologist in the 80s, Mauer decided to become a whistleblower. He took his case to Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, and the story was soon covered by the Washington Post.

Read the Washington Post article >

2001

Audubon Alaska Releases Birds And Oil Development In The Arctic Refuge

Though the case for protecting the Arctic Refuge has often centered on caribou, the coastal plain also provides much-needed habitat for an incredible array of other wildlife. This report produced by Audubon Alaska emphasizes the enormous populations and diverse species of birds that migrate to the Refuge from across the continent and around the world.

2002

Sarah James, Norma Kassi, And Jonathon Solomon Win The Goldman Environmental Prize

On behalf of the Gwich’in people, the trio were awarded this prestigious prize for their leadership in advocating for the protection of the Arctic Refuge and spreading awareness about its ecological and cultural significance.

Early March 2003

Proposed Budget Bill Again Includes Arctic Drilling Provision

Repeating their 1995 strategy, Republican drilling proponents hitch an Arctic development provision to the congressional budget bill. But with Bush in the White House rather than Clinton, refuge defenders could no longer hope for a presidential veto to defeat it.

March 18, 2003

Senator Barbara Boxer Shows Banerjee’s Picture Of Polar Bear On The Coastal Plain

Where pro-drilling politicians dismissed the Arctic Refuge as a desolate and lifeless wasteland, Boxer used images by Subhankar Banerjee and other photographers to demonstrate the vitality and beauty of the region. Much to the dismay of drilling proponents, she successfully convinced her colleagues to vote in favor of removing the drilling provision from the budget bill.

Spring 2003

The Smithsonian Is Pressured Into Censoring Banerjee’s Arctic Refuge Exhibit

Senator Boxer’s use of Banerjee’s photographs brought his work to the attention of drilling proponents as well as refuge defenders. In response to pressure from pro-drilling politicians, the Smithsonian cut descriptive captions from Banerjee’s forthcoming exhibition and relegated it to a difficult-to-find part of the National Museum of Natural History in DC. Numerous publications picked up the story, criticizing the Smithsonian for its suppression of Banerjee’s work and expanding the reach of his photographs and recent book, Arctic National Wildlife Refuge: Seasons of Life and Land.

Photo Credit: Subhankar Banerjee, 2002

April-August 2003

Leanne Allison And Karsten Heuer Follow The Porcupine Caribou Herd On Foot As The Animals Migrate To Their Calving Grounds

Allison’s documentary Being Caribou details their journey from Old Crow, Yukon, to the Arctic Refuge and back, as well as the couple’s subsequent lobbying efforts in Washington, DC. Though it concludes with Allison and Heuer feeling demoralized about the impact of the trip, the film would play a vital role in Arctic Refuge advocacy during the W. years.

Fall 2003 – 2005

Banerjee’s Full Exhibit Is Revived By The California Academy Of Sciences And Tours Throughout The US

Complete with all 49 photos and original captions, the restored show began in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park and then traveled to cities and towns across the United States. Over its two-year tour, Banerjee’s photos helped audiences connect to the Arctic Refuge.

March 2005

Republican Lawmakers Again Sneak Arctic Drilling Into Budget Bill

Senator Boxer repeats her own strategy from 2003 in response, again showing Banerjee’s photos in support of Senator Maria Cantwell’s amendment to remove the drilling provision. But this time the amendment fails with a 49-51 vote, making the intact provision the most serious threat of drilling yet.

September 2005

Gwich’in Conduct Drum-Sing-Dance Vigil At The National Museum Of The American Indian

Sarah James, Jonathon Solomon, and other Gwich’in gather to demonstrate the vitality of their culture by dancing, singing, and beating caribou-skin drums. Attendees of the concurrent Alaska Wilderness Week were encouraged to witness the vigil in action and to support the Gwich’in opposition to Arctic drilling with their own advocacy efforts, including meeting with members of Congress.

Photo Credit: Subhankar Banerjee, 2005

September 20, 2005

Arctic Refuge Defenders Rally On Capitol Hill

The group of 6,000 people from diverse backgrounds gathered to hear speeches from Indigenous leaders, religious spokespeople, elected officials, and others. Together with grassroots mobilizing across the nation, their efforts ultimately succeeded in convincing several moderate Republican House members to change their positions on the budget provision, leading House leadership to jettison the measure in November.

Photo Credit: Subhankar Banerjee, 2005

See footage of the rally >

2007

Catastrophic Drainage Of Zelma Lake In Crow Flats, Yukon Due To Climate Change

The site of Norma Kassi’s family camp and one of the first places Kohm photographed in 1988, the lake’s drainage represents one of many serious impacts that climate change has already had on the Gwich’in homeland.

Photo Credit: Lenny Kohm, 1988

More on the Drainage of Zelma Lake >

Read the 2019 Arctic Indigenous Climate Report >

Summer 2008

Lenny Kohm Presents The Last Great Wilderness Slide Show For The Last Time

Two decades after creating the show at his Sonoma studio, an aging Kohm still remains actively involved in the Arctic Refuge struggle but increasingly devotes himself to a campaign against mountaintop removal coal mining in his adopted home region of the Appalachian Mountains.

April 20, 2010

BP Deepwater Horizon Spill Devastates Ecosystems Of The Gulf Coast

Even though Bill Clinton vetoed Arctic drilling from the 1995 budget bill, his administration approved other anti-environmental measures that benefited the fossil fuel industry and contributed to the escalating climate crisis. These include policies that encouraged lax regulations in the Gulf of Mexico, leading to this catastrophic 2010 spill. At the same time, Indigenous Alaskans showed solidarity to the victims, including Iñupiat Rosemary Ahtuangaruak, who traveled to the Gulf to witness the aftermath of the spill.

Fall 2010

The Rise Of The Tea Party Reveals The Radicalization Of The Republican Party

Efforts to protect the Arctic Refuge had long relied on the existence of moderate Republicans who could be convinced to vote to protect the region. But during the 2010 midterms, many moderates were unseated in their primaries by ultraconservative Tea Party candidates. The period brought climate change denialism and anti-environmentalist fervor to the political mainstream and contributed to the ongoing radicalization of the Republican Party.

2010-2015

Activists Oppose Shell Oil’s Plan To Drill In Arctic Ocean

Resistance to Shell’s massive drilling project came from diverse groups, including environmental organizations and the Alaska Indigenous-led REDOIL (Resisting Environmental Destruction on Indigenous Lands). Shell cited poor initial returns and high operating costs when it abandoned the plan in 2015, but five years of resistance had also made the development seem like bad business.

Read Subhankar Banerjee’s criticism of BP’s drilling plans >

September 25, 2014

Lenny Kohm Dies At The Age Of 74

The many communities that Kohm had touched in his life were shaken by his death. But his memorial service in North Carolina a month later also brought them together. In attendance were Gwich’in leader Luci Beach, who had joined Kohm on slide show tours, as well as other Arctic Refuge defenders and anti-mountaintop removal activists.

2015

Obama Administration Proposes Wilderness Designation For Arctic Refuge

Like Clinton before him, Obama signaled his commitment to protecting the Arctic Refuge from drilling. Yet also like Clinton, his administration consistently encouraged other forms of fossil fuel development in the United States. This included plans to open huge swaths of the nation’s coastlines to drilling—including the North Slope of Alaska—and a willingness to fast-track Shell’s Arctic drilling proposal despite the Deepwater Horizon spill occurring in the same year. Alignment with high-profile Arctic Refuge advocacy has provided a number of politicians like Obama and Clinton a way to burnish their environmental image while supporting fossil fuel interests elsewhere.

Watch Obama’s video statement on the Arctic Refuge proposal >

The Trump Era And The Ongoing Struggle For The Refuge

With the election of Donald Trump and the Republican shift in Congress in 2016, oil and gas drilling on the coastal plain again became a serious threat. But ever since, the Gwich’in and other Indigenous groups throughout the United States and Canada have continued to build alliances and to make environmental justice more central to the climate movement. Indeed, the campaign to protect the Arctic Refuge has become part of a larger, Indigenous-led movement to combat climate change and push for a just transition away from fossil fuel dependency.

Summer 2016

Thousands Of Activists Join The Standing Rock Protest Against The Dakota Access Pipeline

Sparked by Indigenous youth from the Standing Rock reservation, this movement to protect water from pipeline development grew on social media throughout the summer of 2016. At its height, the protest drew thousands of Water Protectors from around the nation to North Dakota, including future New York congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. It also inspired other Indigenous-led uprisings against fossil fuel development.

November 2016

The Election Of Donald Trump Brings A Pro-Drilling Agenda To The White House

On the campaign trail, Trump had vowed to open more lands to drilling and coal mining, while dismissing climate change as a Chinese-devised hoax to impede American growth. He began making good on his campaign promises only days after taking office, quickly expediting oil pipelines, including the Dakota Access Pipeline, and overturning Obama-era environmental measures.

Trump’s Stance on the Arctic Refuge >

Late 2016-2017

The Refuge Short Film Demonstrates The Ongoing Relationship Between The Gwich’in And The Arctic Refuge

Distributed via social media and outreach events, the film features interviews with Bernadette Demientieff and Princess Daazhraii Johnson, current and former executive directors of the Gwich’in Steering Committee, respectively. It shows them planning to attend the 2016 Gwich’in Gathering in Arctic Village, Alaska, and emphasizes how the Gwich’in maintain a connection to the Refuge, caribou, and traditional ways of life.

2017

The Trump Administration Includes Drilling Provision In Its Tax Cuts And Jobs Act Of 2017

In May 2017, Trump’s Secretary of the Interior turned his sights toward the Refuge, stressing the importance of Alaskan drilling for what he called US “energy dominance.” Alaska Senators Lisa Murkowski and Dan Sullivan had been scheming for months to hitch an Alaskan drilling provision to the 2017 bill. With a further-right Republican majority in both houses, refuge defenders were unable to stop the bill before it was signed into law in December.

Learn more about the bill and its opponents >

2017-2020

Refuge Defenders Move Into Other Realms To Fight The Drilling Plan

With the lease of the coastal plain imminent, activists began to seek new avenues to prevent drilling in the Arctic Refuge. Indigenous and environmental organizations mounted legal challenges to the Trump administration’s abrogation of Indigenous rights and the dubious environmental studies conducted by the administration. Others have sought to overturn the Arctic drilling provision through Congress or have harnessed popular support to pressure banks not to invest in Arctic drilling.

Photo Credit: Mladen Mates, 2018

Read more about ongoing opposition to Arctic Refuge drilling >

2018

Green New Deal Proposed In The House Of Representatives

Trumpeted by progressive representatives like Alexandria Ocasio- Cortez, the proposal was at once a legislative policy package, a popular movement, and a theory of social change. Like Kohm’s Last Great Wilderness slide show, it was fueled by a grassroots, ground-up model of activism, and hailed by proponents as a means of addressing the climate crisis and systemic inequalities with integrated policy solutions.

July 2019

Adam Federman Reveals The Trump Administration’s Suppression Of Science On The Impacts Of Drilling The Refuge

Federman’s reporting shows that, after Trump signed the Republican Tax Act in December 2017, his administration rushed and falsified an Environmental Impact Statement required to lease land in the Arctic Refuge. Trump’s Interior Department, like those of Reagan and George W. Bush, distorted data and reversed conclusions to create a report that approved the most aggressive development option possible: to open up the entire 1.5 million acre coastal plain to drilling.

Read the article >

2019

Vuntut Gwitchin Chief Dana Tizya-Tramm Testifies Before Congress

Appearing before a House subcommittee, Tizya-Tramm warned that drilling on the coastal plain would result in the “cultural genocide of the entire Gwich’in Nation.” Along with the mounting impacts of climate change, Trump’s plans to develop the Refuge would make it impossible to maintain the relationships that the Gwich’in had formed with the caribou, lands, and waters of the Arctic over millennia.

Read a Washington Post profile of Tizya-Tramm >

2020

Growing Influence Of Indigenous-Led Movement For Just Transition In Alaska

In addition to spearheading opposition to the tax act’s Arctic drilling provision, Indigenous organizers and leaders have assumed a central role in climate activism in recent years. In Alaska, Gwich’in, Iñupiat, and other Indigenous peoples have joined together to fight against a range of destructive fossil fuel and mining projects. They have increasingly framed the movement as a fight against the environmental injustice of settler colonialism. In its place, they have proposed a just transition toward what Winona LaDuke calls an economy “rooted in Indigenous ecological practices and social values associated with long-term stability.”

Winona LaDuke on the Indigenous-led just transition >

January 6, 2021

Sale Of Drilling Leases For 1002 Area

As insurrectionists stormed the US Capitol, the Trump administration held the first-ever lease sale of the Arctic Refuge coastal plain. Just as the insurrection was incited by Trump’s lies and misinformation about the results of the 2020 election, the Arctic drilling plan relied on the distortion of science and climate change denialism. In June 2021, Trump’s successor, Joseph R. Biden, suspended drilling leases in the Arctic Refuge to conduct a second, more thorough Environmental Impact Statement. Public pressure has delayed drilling in the Arctic Refuge until now, but the future of the coastal plain is still uncertain. The struggle to protect this land continues.

More on the Biden administration’s response >