Since the earliest efforts to protect northeastern Alaska, photographer and filmmakers have played a central role in building support for the cause. In many cases, their images have been effective because they evoke the scenic beauty of northeastern Alaska. During the first campaign of the Alaska Coalition in the 1950s, Olaus Murie and other wilderness activists toured with film and slide shows to build grassroots support for the issue. These images challenged the notion that the Arctic is barren and desolate, instead depicting the vibrant wildlife and diverse environments of the region.

In the late 1960s, efforts to capture the beauty of the Refuge continued when Seattle-based photographer Wilbur Mills was invited by Averill Thayer, the first manager of the Arctic Range, to document the scenery and wildlife of the area during a month-long trip. Many of the photos were carefully planned to capture Arctic wildlife at its most dramatic and vivid. These photos—along with images from subsequent visits—would circulate in conservation magazines throughout the 70s and 80s, contributing a visual element to the Alaska Coalition’s campaign for wildlife refuge status. Mills himself would become directly involved in this cause with series of essays that argued for refuge designation.

In the late eighties, Lenny Kohm found his way to Refuge advocacy through his work as a photographer. While taking photos for an Audubon magazine piece on the issue, he began to build relationships the Gwich’in residents of Old Crow and learn about their way of life. As a result, Kohm’s photos differed from Murie and Mills in that they depict the Arctic Refuge as inextricably tied to Gwich’in ways of life. While some feature still capture wildlife and scenic beauty, many demonstrate the relationship between the Porcupine caribou and the Gwich’in. Though Audubon used only one of Kohm’s photo that featured Gwich’in subjects, those photos and the message they convey would be central to the Last Great Wilderness (LGW) slide show. Synchornizing photography, original music, and narration by several individuals, the LGW slide show would leave a lasting mark on Arctic Refuge advocacy.

Indian-born photographer Subhankar Banerjee first visited the Arctic refuge while taking photographs for a project meant to emphasize the ecological diversity and global interconnections of the Refuge. But with Iñupiat Robert Thompson as his guide, he began to understand the Refuge—and portray it through photographs—as the homeland of Iñupiat and Gwich’in communities. The result was 2003’s Seasons of Life and Land, which was also to be exhibited at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History shortly afterwards. But when Senator Barbara Boxer showcased one of Banerjee’s photos before a Senate vote that killed an Arctic drilling provision, the Smithsonian was pressured to censor his exhibit. The New York Times, Seattle Times, Washington Post, and the Progressive all picked up the story, echoing widespread criticism of the Smithsonian for caving to political pressure. Banerjee would go on to become a vocal advocate for the Refuge and a staunch opponent of other Arctic drilling projects.

In the past decade, photographer Peter Mather has continued to use photos of the Arctic Refuge as an innovative form of advocacy. Photo essays that feature his images add important narrative and framing text, not unlike the LGW slide show, but also reach the significant online audiences of publications like Macleans and the Yukon News.

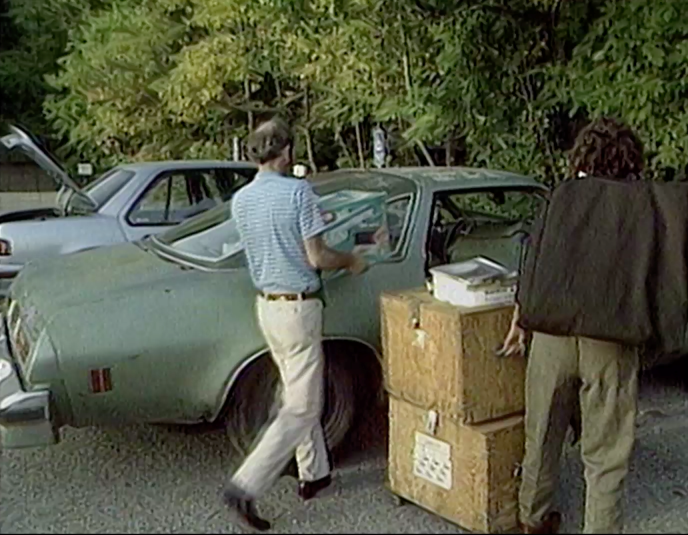

As the threat of Arctic drilling has grown over the past decades, several Refuge defenders turned to film to build support for protecting the area. In 1998, Yukon-based photographer Ken Madsen and musician Matthew Lien produced the multimedia show Caribou Commons: Images and Sounds from the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, which they took on tour with Gwich’in representatives for several years in same vein as the LGW slide show. 1999’s Arctic Quest: Our Search for Truth featured attendees of the 1995 Youth Environmental Summit in Colorado, where Kohm and Norma Kassi had spoken, in a journey to the Arctic to learn more about the drilling issue. Leanne Allison and Diana Wilson’s Being Caribou (2004) follows Allison and her husband, wildlife biologist Karsten Heuer, on a trek from Arctic Village, Alaska to follow the Porcupine caribou herd on their migration to the Arctic coastal plain. Japanese filmmaker Miho Aida’s The Sacred Place Where Life Begins: Gwich’in Women. Speak (2013) centers the voices Gwich’in women as they discuss their ties to Gwich’in customs, the Arctic Refuge, the ongoing struggle to protect it. Most recently, filmmakers Kristin Gates and Jeremy La Zelle have produced two films related to the Arctic Refuge struggle: The Sacred Place Where Life Begins (2019) and Love is the Way (2021).