Since its creation in 1960, the existence of the Arctic Refuge has only been possible because of the efforts of numerous environmental organizations, Indigenous communities, and individual advocates. The earliest efforts to protect the lands in northeastern Alaska from development were inspired by George L. Collins and Lowell Sumner’s “Northeast Arctic: The Last Great Wilderness” published in the 1953 Sierra Club Bulletin. In the following years, a group of mainstream conservation organizations, later named the “Alaska Coalition,” would campaign for the creation of a wilderness area in the region. Activists like Olaus Murie would tour with films and slideshows taken in the region, mobilizing grassroots audiences and pushing the Eisenhower administration to create the Arctic National Wildlife Range in 1960.

As interest in drilling the Arctic Refuge increased in the late 1970s, the Alaska Coalition continued campaigning for legislation to protect it. Again targeting the grassroots, member organizations collaborated on brochures, flyers, and newsletters that encouraged concerned citizens to send letters to or talk to their federal representativs. Many of the materials developed by the Coalition emphasized the array of organizations that had joined forces in support of the cause, leveraging the broad reach that mainstream conservation organizations brought to the partnership. The sale of Alaska Coalition merchandise was also part of the campaign, which supported the cause and spread the message simultaneously. As they had twenty years before, the AC campaign stressed wilderness values in their support for Arctic Refuge protection. They continued to evoke this idea with breathtaking images of the Arctic Refuge, delivered to grassroots audiences through a multimedia tour.

The Alaska Coalition succeeded in passing the ANILCA bill, which created the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and the ‘1002’ coastal plain area. They remained active as new drilling threats emerged in the late 1980s, but by this time a new form of Refuge advocacy had emerged. In 1989, Lenny Kohm, photographer and Sonoma County resident, set out to create the Last Great Wilderness slide show as an organizing tool for the defense of the Arctic Refuge. Like their predecessors, Kohm and the Sonoma Coalition would attempt to mobilize grassroots audiences through intimate showings that featured images of the Refuge. They worked with local and national organizations to host the shows, providing for planning a successful event. Along with these host organizations, LGW presenters and hosts publicized the shows through pamphlets, flyers, newspapers, and other written pieces. Rather than just introduce the issue, they encouraged attendees to take direct political action, providing templates for letter writing and other suggestions and fact sheets to use when contacting their representatives. Members of the Sonoma Coalition, including Kohm and co-founder Glendon Brunk, published their own writing to further the cause.

During his two decades of tours, Kohm worked with the Alaska Coalition and its member organizations, including the Sierra Club and the Alaska Wilderness League, to host, fund, and plan LGW events. But the LGW differed from earlier AC advocacy in that its presenters framed the defense of the Refuge as a human rights issue. Kohm’s own concern developed during the time he spent living with and learning from the Gwich’in in the late 1980s, and the LGW project itself was undertaken with support from Gwich’in leaders. The Porcupine Caribou Management Board helped select Gwich’in representatives that would tour with Kohm and present on their personal experience of the issue.

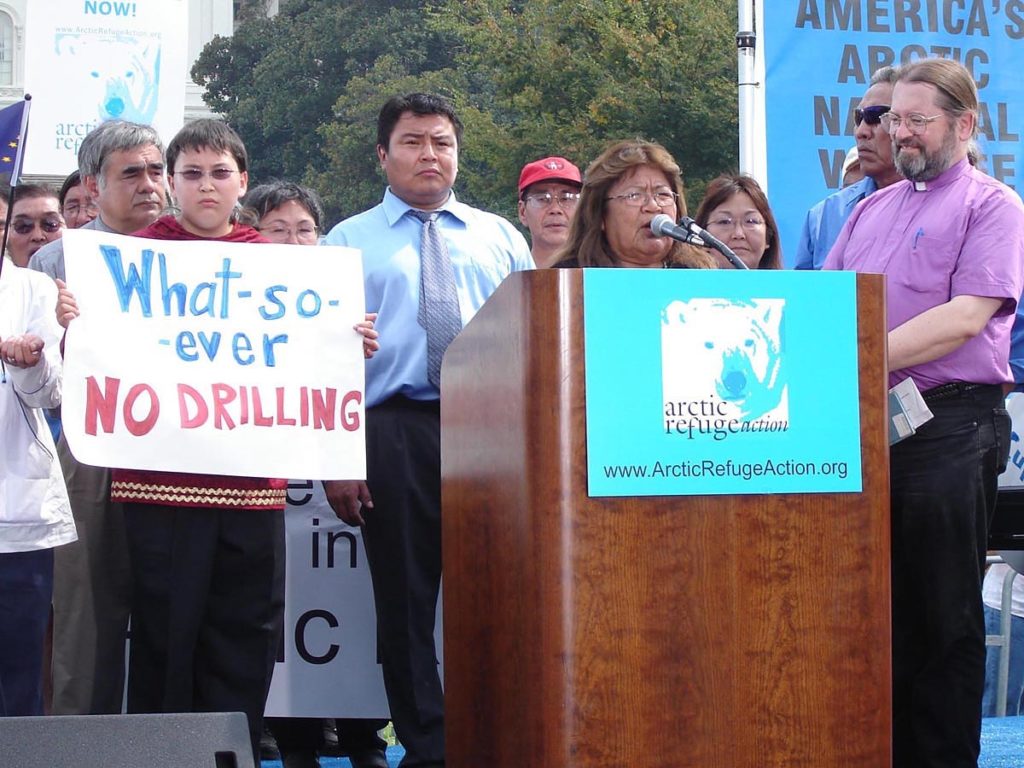

Since the creation of the Gwich’in Steering Committee and LGW in 1989, the grassroots movement to defend the Arctic Refuge has continued to grow and incorporate a broader set of perspectives. On-the-ground rallies and political events have brought together Indigenous leaders, religious spokespeople, and elected officials to address crowds and lead lobbying efforts. More recently, organizers have moved online to reach larger audiences, using social media to share Gwich’in perspectives and engage a new generation in the movement to defend the Arctic Refuge.